“In the struggle, my sympathies were not neutral. But in telling the story of those great days I have tried to see events with the eye of a conscientious reporter, interested in setting down the truth.” – so goes the last sentence of the introduction to John Reed’s (neglected) classic about the 1917 Russian revolution (Ten Days that Shook the World, 1919). I will follow the same principles while discussing the Romanian/Hungarian electricity price bubble of August 2022. This short writing will summarize what happened last Summer and what are the key takeaway points for the future to be better prepared for the next price bubble in the Central European energy sector.

First of all, what is a commodity bubble? The classic economic definition is from a US Court of Appeal judge: “… With fundamentals of demand and supply unchanged, the price of some class of assets skyrocket and then collapse.” (Richard Posner: A failure of Capitalism, 2009, page 85). Bubbles are a sub-category of investor hysteria and have a long history. The Holland tulip bubble (1634-1637) and the South Sea Bubble (1720) are classic examples. The 2008 US housing and credit (double) bubble is more recent and was the starting point for a new sub-branch of behavioral economics (“bubbleology”). The main findings of this brand-new science may be summaries as follows:

- Bubbles always inflate much longer than anybody expects;

- You never know when you are riding a bubble; and

- All bubbles eventually burst.

Commentators also note that bubbles usually start when there is a shift in the perception of future uncertainty (for example, the dot.com bubble) and this is combined with a totally independent, monetary factor (like, low-interest rate). This mortal combination (uncertain future today is less/more challenging than it was yesterday and there is too much/too little money around) may (but not necessarily should) spark a commodity bubble.

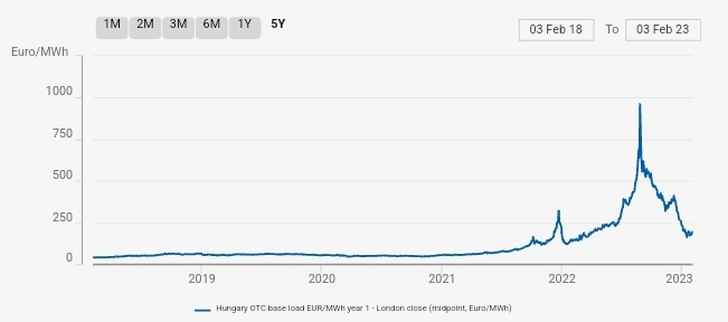

To show you a classic example, here is the historic price curve of the Cal23, base-load, Hungarian (Romanian would look identical) electricity contract:

Source: Argus media

Nothing much happens between 2018 and Q2 2021; then the curve starts moving with a mini-peak (321 euros/MWh) around Christmas 2021. The usual down correction follows in early 2022 (please note the start of the awful Ukraine war did NOT stop this market correction) and finally you can see the bubble in late August 2022. The forward price for Cal23 electricity peaked on 26 August (962 euros/MWh) and then ‘collapsed’ to the 190-180 euros/MWh range. The year-ahead (front) contract has been trading in this range ever since (latest HUDEX closing price: 179 euros /MWh).

How could the price of such a fundamental commodity as electricity fluctuate between 40 euros/MWh (9 February 2018) and almost 1,000 euros/MWh (26 August 2022)? This is a 25x price increase within 1,660 days: on average, Cal23 prices went up by 0.6 euros/MWh/calendar day during this period. This is not normal. What happened? And why has nobody stopped this madness? Where were the regulators (ANRE, MEKH and ACER)?

Going back to the principles of bubbleology, two points should be discussed: What energy traders were thinking about the (near) future during the Summer of 2022? And how much money (credit) was available for forward trading?

Energy trading in the Summer of 2022 was all about the Russian gas supply to Europe. On average, Europe is generating around 21% of its electricity from natural gas. But these EU-27 statistics are rather misleading. For example, the share of gas-fired electricity is below 1% in Estonia, but around 50% in Italy. The Romanian average is around 20%, while Hungary is generating roughly 30% of its electricity from gas. The main problem was (and still is) that natural gas was/is over-dominant in European electricity pricing. The European model for exchange-traded electricity pricing was exclusively focused on the so-called “last marginal unit”: i.e. the hourly clearing price was the offer price for the last MWh generated to achieve supply-demand equilibrium in that particular hour. As a main rule, this last MWh was coming from gas turbines 99.89% of the time. Gas generation is flexible and fast-reacting – both traders and TSOs love this and heavily rely on gas-fired power stations to balance their portfolios. The net result of the above is that European traded electricity prices were/are linked to natural gas: high gas prices translated into high electricity prices, even though only 21% of all EU electricity is from gas-fired power stations.

What was the situation in the Summer of 2022? Russia was systematically and intentionally squeezing gas flows to Europe: although in total six East-to-West international pipelines were available, total volume of gas exported from Russia to the EU collapsed. Compared to the pre-war days, the volume of Russian gas to Europe was reduced to 20%, by the Summer of 2022.

Natural gas pipeline flows from Russia to the Europena Union and Turkey since January 2022. Source: World Economic Forum

So what was the perception of the (near) future for energy traders in August 2022? Very uncertain. Traders were afraid that Russia would stop all gas deliveries, using one or more excuses (like, the North Stream compressors not returning from Canada, or the Russian parliament put the Yamal pipeline on the sanction list, etc.). This perceived gas shortage was pushing forward gas prices over the roof (340 euros/MWh in August 2022), and (as was mentioned above) this gas price hysteria was lifting electricity prices, especially so for forward (Cal23) products. Here was the perfect vicious circle: high gas prices meant high electricity prices, and high electricity prices supported high gas prices. In short, the first ingredient for a commodity bubble (changed the perception of future uncertainty) was there: energy traders were much afraid of the near future. The general idea was that Russia would stop all gas deliveries to Europe, hence panic was the lord and master of trading floors: traders were buying up electricity and gas at any price.

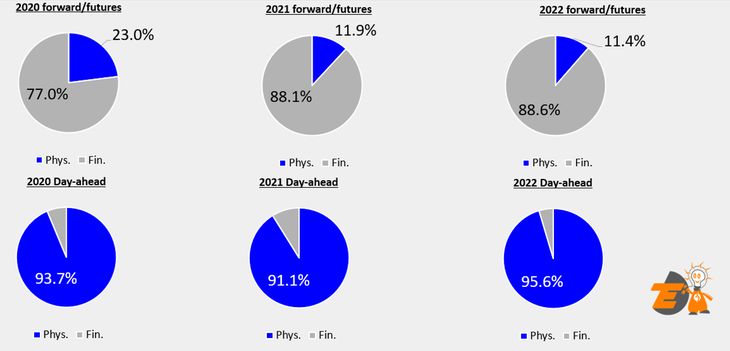

How about the second ingredient, the monetary (credit) factor? Both credit and available cash were in rather short supply last Summer. Energy trading requires a gigantic amount of money – both as cash to pay for electricity/gas, once delivered, and as security (credit support). European electricity trading was transformed into a financial product in 2020.

Ratio of physical (dark blue) trading to financial (grey) Source: T-Energy Advisory Kft

As a main rule, EU traders prefer to execute transactions on exchanges (as opposed to over-the-counter, direct deals with customers). There were several reasons for this switch from physical (direct) trading to exchanges: no counterparty risk (the exchange is the central counterparty to all deals), no licensing (financial trading is not subject to a trading license) and no regulatory supervisory fee and/or Robin Hood (HU)/Solidarity tax (RO).

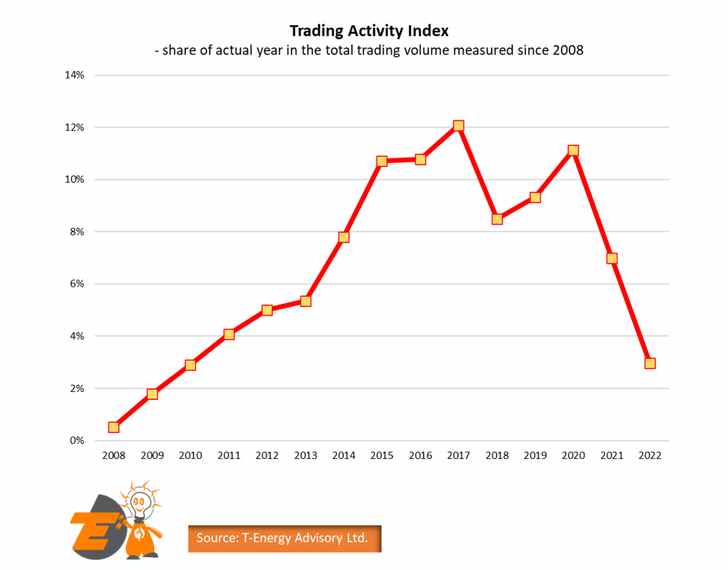

But all of these benefits come with a big price tag: exchange margining. Traders are paying the initial margin, when the deal is done and then variation margins to the clearing houses, as and when requested to do (so-called margin call). Margining turned out to be one of the (big) downsides of financial trading. As was mentioned above, electricity prices were at never-imagined levels by the Summer of 2022: 25x price hikes (compared to the 2018 level) converted into colossal margin calls. The CEO of a Scandinavian trading house mentioned in an interview that in July 2022 his firm was sending, on average, 1 million euros/week to the clearing houses, as margin calls. Like other traders, they sold Cal23 electricity forward to hedge their in-house generation sometime around 2020 (COVID, prices down); and by the Summer of 2022, the margin requirements to hold such sell contracts with 2020 prices (40 euros/MWh) were running into billions of euros, when the forward market was trading in the 900 euros/MWh range. To summarize, cash was fast migrating from energy traders to exchange clearing houses under the code-name “margin call” last Summer. As traders had less and less available cash, they pulled back from doing new deals, and liquidity (traded volume) disappeared.

Hungarian trading activity index (2008 to 2022) Source: T-Energy Advisory Kft

Add together the above two points (very uncertain future + clearing houses sitting on the cash of traders), and you have all ingredients ready for the perfect commodity bubble: scared energy traders without a sufficient amount of money chasing a rapidly diminishing commodity (Russian gas). It was a miracle that European gas prices skyrocketed to ‘only’ 340 euros/MWh and electricity prices to 1,000 euros/MWh.

What could be done to be better prepared for the energy price bubble v 2.1 in Europe?

First of all, the EU should act much faster. Public consultation to reform the above problems has been launched in late January this year only (HERE). This is too little, too late. For example, the above-mentioned EU margining requirements should have been reformed without delay: this level of margining was killing (and not supporting) European energy trading. The European electricity and gas markets are among the most advanced on Earth today; if the European Union would like to secure this leading position, Brussels institutions should react much faster than during the 2022 commodity bubble.

Secondly, the local regulators did (almost) nothing: they were watching the show, as if it would have been a motion picture performance, but did not interfere. Small traders went bankrupt (leaving behind customers with no fixed price electricity and gas – most notoriously, the Budapest street lighting company), and wholesale traders stopped executing deals (liquidity dried up) – what local regulators were waiting for? This high level of passivity is raising the question of whether regulation of wholesale (as opposed to retail) trading should be abolished. For traders, local licensing is an obstacle to market entry, and when there is trouble (like the above price bubble) regulators do not seem to do much to protect the integrity of wholesale trading.

Finally, local politicians, especially so from the national populist league, badly misread the 2022 bubble. They did not (or did not want to) understand that very high prices do not necessarily mean extra profit. Various extra taxes (Solidarity contribution and Robin Hood) took money away from energy traders at that very moment in time when cash would have helped to re-start trading. I have explained earlier (HERE) that special energy industry taxation tends to be expensive, and socially counter-productive: as fewer traders trade less electricity/gas, the more likely that commodity prices will go up. This short-sighted special taxation should be replaced with a new, socially less expensive arrangement.

The final conclusion here is that commodity bubbles are part and parcel of any traded market. As per the above-mentioned bubbleology, price collapse following the burst of commodity bubbles is the natural self-cleansing mechanism of electricity and gas markets. European energy price bubble v. 2.1 will happen, it is only a matter of time. This short writing tried to highlight that plenty of lessons to be learned from the events of Summer 2022. Let’s hope the EU and local decision-makers will be fast enough to re-design European regulation (especially, exchange margining and licensing rules) before electricity/gas prices start spinning again towards the sky.

About the author Jozsef Balogh is a senior business developer for Axpo Solutions, Switzerland, with a special focus on Central European and Ukrainian electricity, gas and CO2 opportunities. He had been active in the Central European energy industry in various roles since 1992. He has been especially active in Ukraine and Hungary.